Scotland's Best B&Bs

There are many wonders of the natural world, and none more so than that of our Atlantic Salmon. Its distribution lies from the North Atlantic, Russia, Scandinavia, the British Isles and into Europe

While some may be familiar with part of the Natural History of the Atlantic Salmon, the following paragraphs may help others understand the life and dangers this remarkable fish negotiates in order to survive.

Atlantic salmon are anadromous – which means they live in both fresh and salt water during their life cycle. The freshwater phase of Atlantic Salmon is usually between one and four years.

This juvenile stage depends on the availability of food such as aquatic insects and water temperature.

Illustration Courtesy of the Atlantic Salmon Trust and Robin Ade

EGG STAGE: Salmon eggs are a reddish-orange in colour, and are laid in fast flowing streams where they lie hidden in the gravel to protect them from predators such as Brown trout who will position themselves down stream of spawning salmon to hoover up any eggs which have not been covered. Incubation can last for more than 50 days where they lie hopefully undisturbed. Water temperature can have a big influence on the incubation period. Colder water means a longer period. The eggs hatch into what is called an Alevin, and now begins the perilous life of the Atlantic Salmon.

ALEVIN STAGE: The young fish (Alevins) still have their yolk sac attached. The sac contains nutrients that the young salmon rely on for weeks or months depending on water temperature. Unable to swim, they remain hidden in their nest (redd) as they are extremely vulnerable to being eaten by predators such as trout, predatory birds etc. The young Alevins stay hidden until they have absorbed their yolk sac, which may be many months, and leave the security of the nest to find their own territory, hiding behind stones etc. to avoid the attraction of predators.

FRY STAGE: Emerging from the gravel having absorbed its yolk sac it is now known as a Fry. Only about 1 inch long these tiny fish are now able to swim and feed for themselves. They leave the safety of the gravel in the stream bed and now fend for themselves in the stream of their birth, for a period of 1-3 years, sometimes longer before they start the journey to sea .

PARR STAGE: When the young fry reaches about 2 inches long it is known as a Parr or fingerling, all this time the young fish are feeding voraciously on insects, nymphs etc. At this stage they are still vulnerable to predators such as our native Brown trout, herons, mink goosanders etc.

Around 2 years old the Parr develop markings called Parr marks. which is the camouflage of the young fish, and helps to avoid predation. Parr remain in freshwater for around 2-3 yrs. or longer depending on many factors such as availability of food etc.

Photos courtesy of Ness and Beauly Fisheries Trust

At this stage the fish go through a remarkable change to enable them to migrate to salt water, this is called Smoltification. They are now referred to as Smolts and become silver in colour, providing camouflage during their marine phase, this change allows them to adapt to life in the ocean where they will travel to their feeding grounds in the North Atlantic.

This Smolting stage in a salmon’s life is a dramatic one. The smolt migrates to the coastal estuaries and are busy making the physiological changes to survive at sea. The young salmon will gather in shoals in the lower river during the early summer months, before starting their long and perilous journey to their feeding grounds in the North Atlantic. During this time, they are subject to predation from seals and birds such as cormorants, other fish and of course as a bycatch by trawlers while fishing for other species. Having reached their feeding grounds around the west of Greenland, they will remain there for two to four years putting on a great deal of weight. After which, they will start the journey back to their natal river where they were born. Although some fish will feed around Iceland, these are called Grilse and will return after one year at sea and will weigh between 2-3 kilograms. While the fish returning from Greenland after two to four years at sea, will generally weigh between 3-10 kilograms, some will reach 20 kilogram or more.

When they return and enter their river of birth, the salmon stop feeding and rely entirely on the reserves of fat built up during their feeding at sea. As salmon enter our rivers most months of the year, this period may only be a few weeks, however, as in the case of spring Salmon can be as long as 10 months before finding a mate and spawning. The returning salmon make their way to the burn of their birth and indeed to the exact spot they themselves were born. We know this by the genetic footprint of returning salmon and their offspring.

Salmon leaping on the River North Esk, photo by Gordon Nicoll

Having negotiated waterfalls avoided otters and mink, the female (hen) eventually lays her eggs in an area of gravel/pebbles known as a red. The male (cock) lays alongside to fertilise the eggs with his milt. The male has by this stage put on his spawning colours to attract a mate and has grown a large hooked jaw known as a Kype, which he uses to fend off any other suitors for his mate.

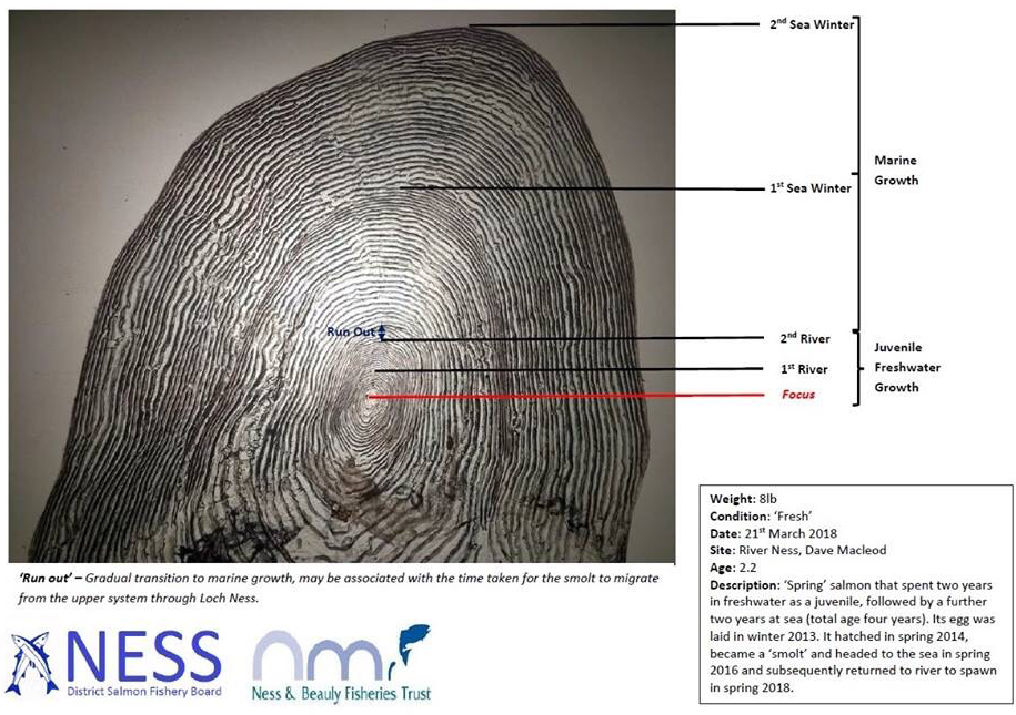

Many of the males do not survive afterwards but many hens are able to swim back to sea, where they are known as Kelts. They are very thin and are not strong swimmers because they have not eaten for many months. When they reach the sea once again, they are prone to being eaten by seals, dolphins and larger fish such as cod so few hen fish return to their river to spawn again. Any fish that do survive this epic journey a second time are known as multi-spawners. Just like the rings of a tree a Salmon’s complete life cycle can be determined by biologists, by reading the scales of an individual fish.

The diagram below shows the identifying rings indicating the different stages in the salmon’s life.

Diagram reproduced courtesy of Ness and Beauly Fisheries Trust

4 Star GOLD B&B near Dufftown, north-east Scotland

Contact Ian Sharp

Email: [email protected]

Tel: 01340 820941 / 07747784462

Sign up to Scotland's Best B&Bs Newsletter to receive our Latest Offers and Packages.

Please feel free to share the content of this page with your friends – simply click on where you would like to share it.